Only took me 20 years…

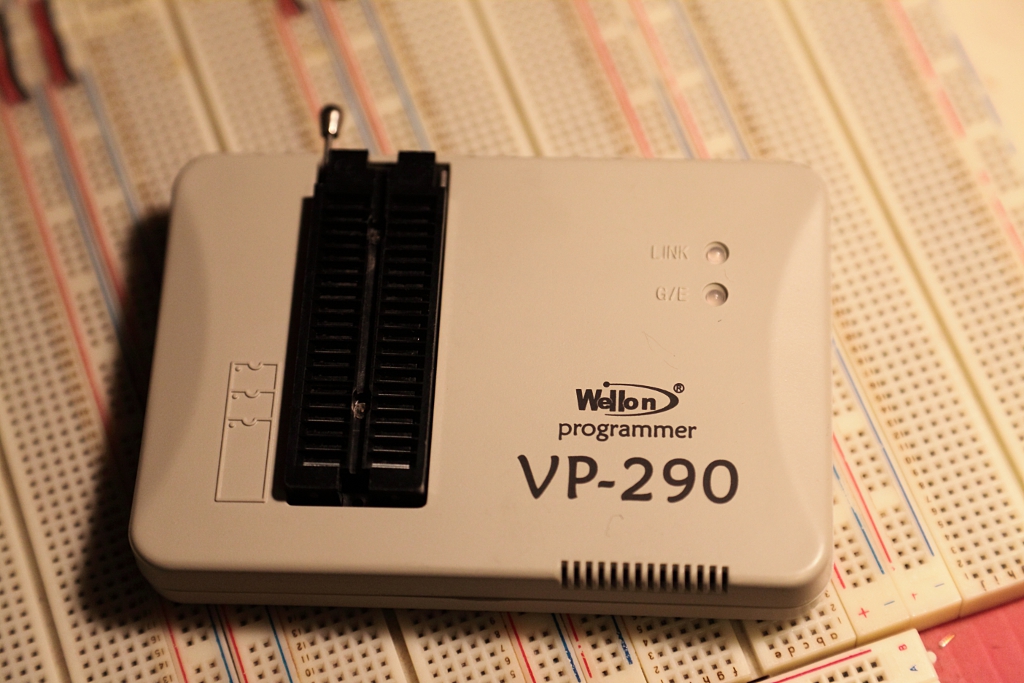

The latest addition to my mad science lab: A device programmer.

There’s a lot of history behind this purchase.

Back when I was taking Electronics Engineering Technology in Toronto, twenty years ago, we had to do a sort of “mini-thesis” project in our final year. I really wanted to make an EPROM programmer for my project, because having one would enable me to incorporate stored-program components like microprocessors into my electronics hobby projects, and I couldn’t afford to buy one.

The instructor (hi, Darrell!) said this project wasn’t complex enough and would only be worth a ‘C’ grade at best, so I was forced to choose something else. But I’ve been wanting a device programmer ever since.

Lately I’ve been having a hankering to dust off the hobby and do some projects, and being able to use programmable devices is necessary for many of the projects I have in mind. I thought about making my own again, but I decided to check and see if prices on commercial models had got a little more reasonable. While I place value on doing stuff myself, making my own is now less interesting than the things I can do once I have one, so I’m willing to sacrifice some nerd cred in order to get to the good stuff faster.

Prices haven’t improved (most professional models are still in the thousands of dollars) but there are some cheap alternatives available now. I looked at what could be had from local dealers and from eBay, and I was tempted by these things called Willem programmers. They typically plug into a PC’s serial or parallel port, though some models now support USB, and they’re super cheap.

Unfortunately upon doing some research, I found that buying a Willem looked risky. Willems started out as a hobbyist design, which got picked up and mutated by others. There are now dozens of different models, many of which do not come with documentation or with functioning software – the Willem name has become so fragmented that there is even a visual identification guide to try to help people figure out which one they’ve got, so they can try to make it go. There are also some unscrupulous dealers doing things like naming their products “True Willem Programmer” to make it sound more credible than it is (“True” is part of the name, not a description).

So I could go cheap and buy a Willem and risk having to spend a lot of time hunting down software, or maybe even reverse-engineering the thing to write my own, or I could drop a little more on a prosumer model. I settled on the Wellon VP-290 pictured above after reading some favorable reviews on hobbyist websites, and a brand new one set me back less than $200. It has an impressive list of supported devices, which more than covers my needs.

I haven’t actually burned any devices with it yet – I haven’t decided on my next project, let alone written the firmware. But I did test the programmer by reading out the contents of some old EPROMs I had sitting around, and while the software workflow isn’t slick, it’s good enough. I think this will prove to be a fruitful purchase.

So: I’m letting out a long sigh after twenty years of holding out. I had a lot of emotional investment in making my own device programmer – that initial rejection of the project idea got my hackles up and I never forgot it. But time heals all markets, and I’ve finally put it to rest and enabled myself to move on to bigger and better projects.

Solaris: Book vs. Films

The 1972 film Solaris has long been one of my favorite science fiction movies. Mainly because of the concept of Solaris itself, but also because of the oddities of Russian filmmaking and its extreme length, both of which made the set of people who have watched it something of an elite club.

This last week, I finally set out to read the original book by Stanislaw Lem, and re-watch both of the films based on it. I had somehow never got around to reading the book before, and when I last saw the 1972 film I was too young to fully understand it. By the time of the 2002 film, I certainly understood it but was left with the feeling that it really diverged from the original vision, which is what prompted me to eventually do this comparison of the three.

There is a big difference. Lem was upset with the first film and I can see why. Both film adaptations use the trappings of the book to tell a different story, and largely miss what the book was about. The films are two different versions of the same love story, set in space, with Solaris simply being a setting that enables the strange situation of a man being confronted with what seems to be his dead wife, and all the mystery and angst that comes out of this apparent second chance.

I’m not saying the movies are bad. They’re both excellent films that tell engrossing and touching stories, but they’re not the original story. These are stories about people, which is fine since those tend to make for good movies, but they ignore the seven hundred billion ton elephant just outside the room.

Solaris, the book, was about questioning what humans as a race want from the universe. Science fiction is full of humans zipping around space, fighting and colonizing and meeting aliens and having a good time or getting eaten by monsters. Those are all pretty familiar and easy to understand things because they’ve happened on Earth in the past – we’ve gone zipping around the oceans, fighting and colonizing, meeting other flavors of humans and having a good time or getting eaten by tigers.

In Solaris we meet something truly alien – and what I love about Solaris is that it’s by far the most credible alien I’ve encountered in my life of reading the watching science fiction. Here’s a life form the size of a planet, larger than Earth. Apparently intelligent. Not an organism as we understand it – it’s not made of cells, but instead is a planetwide ocean of chemicals. Have you ever flown over the ocean and looked down at the endless deep water with its tiny waves? Imagine all that water was part of a giant brain. What commonality do we have with a being like that? How could we possibly communicate with it, and should we even bother trying?

Part of the setting in the book is about this – humans have been studying Solaris for decades already and making exactly zero progress. Solaris is certainly active – it reacts to their presence. It also manifests structures out of its soup, some of which appear to be models of things it knows about, including humans and mathematics, but these appear to be part of its thought process rather than communications. Human attempts at communication go nowhere – it may not know what communication is or may not have any motivation to communicate, or it may be trying to communicate and we just can’t recognize it.

After smacking their heads into this wall of alienness for so long, the characters in the story articulate how the communication effort reflects back on humanity: We don’t really know what to do with other planets and other beings, except convert them into more of the same – more Earths, more varieties of humans. The first time we run into something that can’t be hammered into any of the familiar pigeonholes, we don’t know what to do. The characters end up speculating to try and satisfy themselves, but it gains them no additional truth or understanding.

Best of all, there is no conclusion. Both of the movies have an ending that says what happens to the protagonist from then on, but the book is open-ended, and I prefer it that way. The story is meant to cause contemplation, and putting a bow tie on it removes the trigger for contemplation, which is the act of wondering what happens next.

I’m also disappointed that neither of the films attempt to render the visual richness of Solaris – making the films character stories certainly cut the effects budget by a lot. Solaris as described in the book is full of visual richness, with a wide variety of forms appearing on its surface ranging from barely comprehensible to completely incomprehensible. The hard science fiction nerd in me wants to see those things – I wanted a film about the what rather than the who. A future-documentary about Solaris would be just the thing.

To sum up, all three versions are great, but only the book is the true Solaris – the films are relatively pedestrian people stories in which the one truly special thing about the book is ignored and could be replaced with some other plot device, like a capricious wizard or standard little green men from Mars.

What I’ve Been Reading: Christopher Alexander

This post is a bit delayed. Over the course of two years, ending last year, I read Alexander’s three-volume set:

Volume 2 is somewhat famous in computer science as presenting an alternative way of thinking about design patterms, and there are people who wish for a way to apply similar thinking to software patterns.

I decided to read the book to see what the fuss was about, and I have some interest in architecture myself anyway. I decided to read all three volumes to get the complete picture. It was a lot of work – interesting as they are, these are voluminous and dense books.

Volume 1 makes the case for the need for a design language in architecture, with which to discuss the design of all types of buildings and human environments. Volume 2 builds the vocabulary of the language by proposing hundreds of design patterns, which are sort of the words and phrases of this language, and volume 3 discusses an attempt to put this all into practice.

I can’t really say anything meaningful about how this all applies to computer science. In a way I’m still digesting the philosophy presented in this work and it may be that I’ll never “get” how it might best be applied to my own profession, but I totally get how it applies to architecture because it’s presented largely in opposition to the architectural mistakes of the previous century. It’s all about making work and living spaces that are functional, versatile, and above all, comfortable and not dehumanizing. Putting the people who use a space ahead of flashy design or cheap construction.

I do recommend reading volumes 1 and 2; just realize doing so is a big project that requires contemplation. Volume 2 could actually be toilet reading for a year – most of the patterns are about 3 pages.

Now I’d like to share some quotes, summaries and excerpts from volume 2 that resonated with me. Some of these are practical and some are more philosophical.

On the subject of learning environments for children: “In a society which emphasizes teaching, children and students – and adults – become passive and unable to think or act for themselves. Creative, active individuals can only grow up in a society which emphasizes learning instead of teaching.” (Page 100) This feeds my feelings about public education and the difference between force-fed learning and natural, curiosity-driven learning.

On room placement in a house: “[In the Northern hemisphere] place the most important rooms along the south edge of the building, and spread the building out along the east-west axis.” (Page 617) This, combined with another pattern that requires sunlight access from two walls of each room, increases the amount of sunlight in the most lived-in rooms, which is good for improving the mood of the home.

Rule 129 (page 618): “Common Areas at the Heart” (with pathways tangent). This rule says that the common areas of a home or workplace, such as the living room or break room, should be near a central point of convergence of the walkways, but should not actually overlap a walkway – it should be possible for people to walk by and see what’s going on without becoming involved or interrupting anyone.

Rule 130 (page 622) describes the importance of having an entrance room – a room that you pass through when entering and leaving the house, where you put on or take off outdoor clothes and do your greetings and farewells. I think this is really important because I’m often frustrated by home designs that don’t have this – I need space to sit down to take off my boots or tie up my shoes, and there should always be room to place an empty coat rack, shoe rack and umbrella stand so your guests don’t have to root around in your overstuffed hall closet.

“The movement between rooms is as important as the rooms themselves; and its arrangement has as much effect on social interaction in the rooms, as the interior of the rooms.” (Page 628); “As far as possible, avoid the use of corridors and passages. Instead, use public rooms and common rooms as rooms for movement and for gathering. To do this, place the common rooms to form a chain, or loop, so that it becomes possible to walk from room to room – and so that private rooms open directly off these public rooms. In every case, give this indoor circulation from room to room a feeling of great generosity, passing in a wide and ample loop around the house, with views of fires and great windows.” (Page 631). I agree with this – corridors are sometimes necessary but they’re also often a waste of space.

Page 639: “Place the main stair in a key position, central and visible. Treat the whole staircase as a room (or if it is outside, as a courtyard). Arrange it so that the stair and the room are one, with the stair coming down around one or two walls of the room. Flare out the bottom of the stair with open windows or balustrades and with wide steps so that the people coming down the stair become part of the action in the room while they are on the stair, and so that people below will naturally use the stair for seats.” Ever watched a movie where people in a posh house are having a conversation while some of them are sitting or standing on a nice staircase, and secretly wished for such a nice room? Yeah, they don’t make staircases like that anymore – in most modern houses I’ve seen, the main stairs are only as wide as they need to be and are only intended for climbing, and tend to be part of hallways rather than rooms. The stairways we want are in a room, are not blocked off halfway up by part of the second floor, and have a flared bottom that invites sitting and also is convenient for heading to and from the stairs in a variety of directions.

Page 646: “Create alternating areas of light and dark throughout the building, in such a way that people naturally walk toward the light, whenever they are going to important places: seats, entrances, stairs, passages, places of special beauty, and make other areas darker, to increase the contrast.” Hell yeah. I can’t say I often see cases where lighting is done horribly wrong, but this makes so much sense that it should be kept firmly in mind when designing your lighting.

Page 657: “Sleeping to the East: This is one of the patterns people most often disagree with. However, we believe they are mistaken.” It goes on to make the case that being awakened by sunlight and having the sleeping place dark in the evening is probably good for our health, and it makes a lot of sense to me. I can’t put it into practice because of the timing requirements of the lifestyle I’m currently in, but I would like to give it a try some day, like when I’m retired or self-employed.

Pattern 140, “Private Terrace on the Street”, on page 667 presents a surprisingly simple bit of landscaping that can increase your privacy in your yard and your front room: Raise the the base ground level of your yard a foot or two above street level, and then add a low fence to that. The net effect is that your eye level will be above the fence and above street level so you can see what’s going on, but the fence will be at or above eye level for pedestrians and drivers, so they won’t have as good a view of you.

Page 734: “The experience of settled work is a prerequisite for peace of mind in old age. Yet our society undermines this experience by making a rift between working life and retirement, and between workplace and home.” Yes. To me, a joyful retirement means getting to work on what I want, when I want – not just sitting around or traveling to kill time. A home for a happy old person is one that has space to be creative, not a box where you wait to die.

Page 834: “Everybody loves window seats, bay windows, and big windows with low sills and comfortable chairs drawn up to them.” Very important. In almost all the homes I’ve seen that have big bay windows off the living room, they’re ignored and unused, and the windows are kept closed. They tend to be set up such that opening the big windows reduces your privacy too much, and most people organize their living rooms around the TV so there’s no room left for a comfy reading chair by the window.

Rule 196: Corner Doors (page 904): “The success of a room depends to a great extent on the position of the doors. If the doors create a pattern of movement which destroys the places in the room, the room will never allow people to be comfortable. […] Except in very large rooms, a door only rarely makes sense in the middle of a wall. It does in an entrance room, for instance, because this room gets its character essentially from the door. But in most rooms, especially small ones, put the doors as near the corners of the room as possible. If the room has two doors, and people move through it, keep both doors at one end of the room.” I think this makes a lot of sense – you can’t really get settled in a room if other people are always walking through your space, regardless of what you’re doing.

Another problem that I’ve noticed with current Western house design, which touches on several of these patterns, is that the main entrance is often unused. This is especially true on the prairies – people use the kitchen door, garage door or back door for entering and exiting and almost never use the main front entrance because it doesn’t serve their practical needs. Any home design where a major feature is unused is a major failure because it fails to consider the needs of its occupants.

What I’ve Been Reading

Vancouver Noir by Diane Purvey and John Belshaw. This caught my eye while I was on a bookstore crawl and I bought it on impulse, mainly because it seemed to have some nice historical photos of Vancouver.

It’s pretty interesting – Vancouver has a somewhat seedy history that I was completely unaware of, but now that I’ve read it I can sort of see why some areas of the city are they way they are today. It was interesting to learn some historic events involving hotels that still stand today, and watch the evolution and motion of the downtown core.

One thing really annoyed me about this book – an apparent lack of editorial oversight. The words “discrete” and “discreet” were consistently confused in the few places they were used, and I have a feeling there were some past/present tense flip-flops going on though I didn’t pay close enough attention to explicitly note them.

Overall it was a fascinating read though, and the pictures are indeed interesting.

—–

Greg Egan: Axiomatic and Luminous

Being two short story collections, the first collected in 1995 and the second in 1998. I’ve liked all of Egan’s novels so far, but my biggest comment about these short stories is that they seem awfully formulaic. A lot of them follow the pattern of establishing a character who has some interest in the nature of mind, will or identity, then introducing a plot device that allows exploration of one of these themes, and then ending with some sort of ironic or otherwise revelatory twist that results. To be fair, this is partially symptomatic of the short story format, and since the stories were probably originally published at different times and in different fora, the similarities would not have been so apparent until they were collected.

There were a lot of good plot device concepts, such as a biofeedback device that would let you visualize your brain activity in real time, or a brain replacement that learns to be you by successive approximation over the course of decades.

There were also some bad plot devices – things that I could let slide as a concept to be explored as a story, but otherwise were pretty bad science. Like predicting the future by looking at a time-reversed image of the galaxy through a telescope. Or the claim that a simulated person could have experience during the construction of the simulation, before it was actually run – that’s just plain impossible, and the way it was written it almost seemed to be begging the existence of a supernatural “soul”.

A few of the endings were a bit predictable too, like where buying cheap knockoff products gives not quite the desired result. A couple of the stories were incomprehensible to me – I just didn’t get the point at the end – presumably because they were ones that touched on religious themes.

Some of the stories were good, and the common theme of exploring the nature of self and mind is very appealing to me, but overall I prefer Egan’s full-length novels.

—–

L.E. Modesitt, Jr.: The Eternity Artifact – Chosen because it sounded like exactly the sort of story I felt like reading at the time. Space opera with mysterious deserted alien cities to be explored and artifacts to be found and human enemies to be outwitted. The ending was not what I expected, but it wasn’t disappointing. Pretty decent read.

Modesitt chose to create a familiar political climate for this far-future story by creating a back-story involving a diaspora from Earth at a time when there were still strong national and religious groupings, so the major types of religions and political systems tended to end up controlling groups of proximate solar systems and then warring with each other the same way they did when they lived in countries instead of on entire worlds.

The author casts the descendants of Christian-like and roughly-Islamic groups as the major villain-groups of the story, which was a pleasing surprise. The secular protagonist civilization is questing after the first alien relics ever discovered, which are clearly from a much more advanced civilization, and the religious groups really don’t want this to happen, because either the relics are one of the biblical superweapons left by God or Satan, in which case they must either be secured by the righteous or sealed away forever, or they’re not, in which case Man is not God’s foremost creation – which is an idea is a major threat to the core beliefs of the pseudo-Christians especially.

—–

Robert L. Forward: Martian Rainbow – Seldom have I been so disappointed in a hard SF story. This one is unusually shallow and contrived, even for Forward, who has a tendency to produce what I call “tech demo” stories – hard SF that is even harder on the speculation and thinner on the characterization than usual. This is not to say that kind of writing is always bad – I’ve enjoyed most of Forward’s other books.

The story here is: Earth conquered by madman, Martian bases left to fend for themselves with insufficient resources, madman threatens survival of human race, Martians find self-replicating nanofactories left by original inhabitants of Mars, use them to save day for everyone and terraform Mars too.

The madman’s conquest of Earth through a cult of personality reinforced by masterful religious propaganda and political manipulation was way, way too fast and easy to be believable. Also the fact that the PR and technical wizards that enabled his rise to power were so fatally blind to his insanity. It basically boils down to “everyone loves the war hero and believes him when he says he’s God and lets him become dictator of Earth.”

The other side of it is the Martian tech that saves the day. These are mobile machines (initially mistaken for organisms) that can eat anything and manufacture almost anything, including diamond in any size and shape you want, while producing no harmful waste products. They can also produce more of themselves as needed, and multiply their computing power by linking up in a chain, and do so in order to learn human language overnight. How awfully convenient if your survival requires rapid terraforming of Mars and you also need to pull a miracle out of your ass to save Earth from destruction. But all this isn’t the part that bugs me. Many of Forward’s stories are contrived around biological or technological oddities. What bugs me is there’s no back story here. The interaction between the humans and Martians machines amounts to:

- Humans: “Here’s our language files.”

- Martians: “Hi. Excuse us while we get back to tending our plants.”

- Humans: “Hey, if you don’t mind, we could really use a hand converting your planet into something we can live on.”

- Martians: “OK.”

- Humans: “Just like that? Won’t this affect you?”

- Martians: “It’s unthinkable for us to refuse any request or interfere with your survival, and your request doesn’t contradict our masters’ orders.”

- Humans: “Where are your masters?”

- Martians: “They went away, and we’re not allowed to tell you anything about them.”

- Humans: “OK. Get to work.”

- (time passes)

- Humans: “Hey, that bunch of Martians is going to get themselves killed! We don’t want any of you dying for us!”

- Martians: “Even though we’re obviously intelligent and autonomous, we’re machines and not alive so it’s OK.”

- Humans: “Oh, carry on then.”

So basically there’s a tantalizing mention that some aliens built these extremely capable machines and then left them behind to do menial tasks, but there’s absolutely no attempt by the humans to weasel out more information about the aliens or find it by other means. There are just token gestures as to how humans are awfully nice and considerate even when in dire straits, and then the alien machines are used to bludgeon into the reader how powerful the concepts of exponential growth and molecular manufacturing are.

The ideas here could have gotten a better treatment if the book were twice as long, but it would still need these rough edges filed off.

Life on (our) farm

People seem to be amused when I tell tales of my life in Manitoba, so I thought I’d post a more detailed account with photos.

In the early 1980s my parents purchased 80 acres in rural Manitoba, with an ancient log cabin on it, and we moved there. I think we stayed for most of three years, and then again for a couple more years in the early 1990s. Today I’ll just talk about the somewhat rustic living conditions I had the pleasure of experiencing.

The cabin was a small three-room affair built of logs and insulated with a mixture of mud, straw and manure, which was common in the pioneer days (judging by what the neighbors told us, this cabin was probably built around 1900, give or take a couple of decades). The attic was of slightly more modern construction, having wooden shingles, a cut lumber frame and adding a finished wood ceiling to the ground floor. It hadn’t been lived in for a long time when we arrived; the windows and doors were long gone and birds were nesting inside.

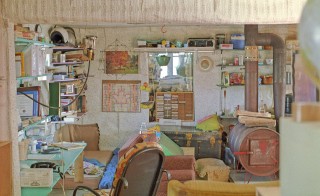

These photos, taken when we were unloading our moving truck, give some idea of what it looked like and the finish on the walls:

The first thing we (meaning my father) did to make the place habitable was to knock out all the mud insulation

and then fill in the gaps with modern insulation, install doors and enlarged windows, and wrap the outside walls in plywood to deflect the wind. He also knocked out the interior walls to make it feel more spacious, so there was just one room downstairs and one up. After all that, the house looked like this:

Here’s what the interior looked like after we moved our stuff in.

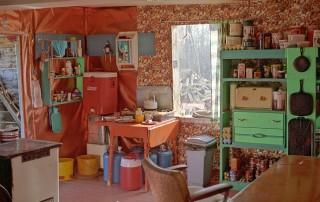

There was no electricity here, and we couldn’t afford to get it installed. On the table to the right you can see a couple of the oil lamps we used for lighting at night.

To brighten things up, we painted the floor and wallpapered the interior with light colored wallpaper and shiny foil. Later we got a Coleman gas lamp, which was really bright but also made a lot of noise and gave off fumes.

In the above picture you can see the oil drum stove my father made – the wood-burning kitchen stove we bought (shown in the kitchen photos below) was insufficient to heat the place in the winter, though it made great bread. If you look closely at the photo below, you can see that we also brought in the propane cookstove from our camper – but that was only good for cooking things and not for heating. We preferred the propane stove for summer cooking because it didn’t produce excess heat and didn’t take time to get going, but the wood stove was essential in winter.

There was no water here. The well that had once been on the property had filled itself in. No streams, and lake and pond water is dangerous to drink. We also couldn’t afford to have a new well drilled, so we had to truck it here ourselves in 5-gallon camping jugs, seen under the orange table in the upper photo. Nearby water sources weren’t reliably clean, so most of the time we got our water from the town of Rossburn, which was about 25 miles away. In the first kitchen photo above, in the corner you can see an antique washing machine that we used to store washing water, and the big camping thermos on top of it was for drinking water. The orange pails on the floor were used to take waste water outside.

No water means no plumbing, of course, and without electricity you do not want to have to use an outhouse in the winter here. Our toilet was a big pail with a seat on it, placed near an upstairs window with a view of the woods, and with a curtain on the indoor side for privacy. It had to be emptied about twice a week. Bathing involved standing in a kiddie pool and pouring water on yourself from a bucket using a cup. Here’s the bathtub set up in the kitchen, as verified by our cat:

In winter we could melt snow for bathing water, so we didn’t have to make water runs quite so often.

The one utility we did get installed was a telephone, which was essential for my father to find work. It was a party line, shared with our two nearest neighbors (1/2 mile and 1 mile distant, respectively). Incoming calls signaled the intended household with distinctive rings – short ring for one, long ring for another, and two long rings for the third. If you wanted to make a call you had to first pick up the handset to verify the line wasn’t already in use. Occasionally a change in the line noise made us suspect that one or another of the neighbors was eavesdropping on our calls.

We also had a battery-powered radio. CBC national radio was pretty darn good in those days, and we passed a lot of time listening to Peter Gzowski’s “Morningside” talk radio, Lister Sinclair’s “Ideas” for science news, Arthur Black’s amusing “Basic Black” op/ed show, and Jackie Farr’s weekend comedy hour “The Radio Show”. I still think of Peter Gzowski as the voice of Canada – there’s no voice that better represents Canadian culture in my mind.

The final major improvement we made was a greenhouse, which my father built using surplus glass from a construction site in Calgary, and old lumber from a derelict barn nearby:

With this and an outdoor garden we were able to grow some of our own food. I also grew flowers, including some giant sunflowers, one of which eventually reached a height of 14 feet.

Our sleeping area was in the attic – we usually slept in individual sleeping bags, zippered up, to help keep the bugs and mice out of our beds. (We would occasionally find a garter snake in the house too, but they never came upstairs, thankfully.)

There was a problem with reading at night though – dozens of brown moths would work their way in through the roof shingles and throw themselves at the oil lamps we usually read by. Not only was it startling and irritating to have moths landing on your head or book while trying to read, it was a bit of a fire hazard because sometimes they would succeed in their attempt at glory, and would fall inside the lampshade and burst info flame – and on rare occasions this heat imbalance would fracture the lampshade too. I switched to using an electric light powered by a car battery, but that required idling the truck to recharge the battery every other day.

We stapled plastic sheets to the inside of the roof to try and keep the moths out, but it wasn’t enough. Eventually I put my bed inside a tent in my wing of the attic, so I could read with only my face and arms poking out, and sleep with the screen closed. Yes, I regularly slept inside a tent inside a house, for practical reasons.

My bedroom, bed-tent on the left. Note the plastic sheeting on the roof, which was not enough to keep the suicidal moths out.

It got a bit chilly here in the winter. We only spent one full winter here, and thereafter found reasons to be elsewhere during the coldest months. Waking up with frost crystals where your breath fell was common enough, but that one Christmas morning we woke up to find the temperature -50°C outdoors, and -30°C inside the house. We spent most of that day either in bed with long underwear and multiple socks on, or in full winter gear with our booted feet in the oven to help warm them up. I don’t think the interior temperature ever got above freezing that day. This is my “get off my lawn” story for Vancouverites or foreigners who complain about it being cold even when water is still liquid. If it had been much colder in Manitoba, we would have had to break off and melt chunks of air to breathe, ya softies! You haven’t experienced a Canadian winter unless you’ve had to light a fire under your vehicle to thaw out the oil so you can start the engine.

There was no rural mail delivery in Manitoba then, though I gather there is now. We had to drive 12 miles to the nearest town, Angusville, to pick up our mail and do our banking. That was a town of about 200 people, and all it had was the post office, bank, a cafe, two mechanics, a small general store and a hotel that wasn’t rebuilt after it burned down. Most of those services are gone now.

We got most of our supplies from the town of Russell, which was about 30 miles in the opposite direction from Rossburn. We made a weekly trip to Russell to get groceries, household goods and to do our laundry, and to entertain me – this town was large enough to have a pizza joint with attached arcade, a pool hall with arcade games, an indoor theater and a drive-in theater. Here’s what the main street looked like back then:

There were two large grocery stores, a clothing store, a Sears catalog outlet, a hospital, a small library, two hardware stores, a drugstore and a couple of passable restaurants – all the luxuries you could want. I tried to spend as much time as possible in the arcade because it was the only chance I got to play video games.

Thanks to its proximity to a valley with hills suitable for skiing, Russell has managed to play up tourism enough to avoid the zombification that has claimed most prairie towns. I returned there recently on my cross-Canada road trip, to see how things had changed. Since we left, our cabin has suffered a lot of deterioration. Animals have broken in through the decaying roof, and the interior is now a disaster zone. I wouldn’t want to go in there without a hazmat suit. Here’s what it looks like from the outside now:

The green thing on the right is the wooden camper my father built, which you might have noticed him removing from the back of the truck in one of the photos at the top. We lived in this now-stationary camper while fixing up the house. The camper is now a giant camper-shaped ant colony.

Overall, despite the rustic conditions, I rather enjoyed my time in Manitoba. It was certainly character-building, anyway. Now, as an exercise for the reader, imagine spending your late tweens and early teens in a place where the nearest other kids were 1.5 miles away and you didn’t see them at school because you were homeschooled. And there was no TV or video games or computers, because no electricity. Radio, music cassettes, books, comics and Lego were what I had. Plus the great outdoors, my family and pets, of course.

I haven’t talked at all about why we moved here, what we did while here, what there was to do in the area, who we interacted with, or why we left. Maybe some other time.

To give you the lay of the land: Map