What I’ve Been Reading

The Heritage Universe quintilogy by Charles Sheffield

A very fun adventure series set against the common background trope of a mysterious vanished alien civilization having left amazing and incomprehensible toys behind for the younger civilizations to puzzle over. The arc follows a gang of human and alien characters with a healthy mix of motivations as they get caught up in events that lead to some answers about the long-vanished Builders.

The first two books in this series don’t stand well on their own, but they work well in the context of the overall arc. At first I didn’t like that Summertide didn’t really reveal anything about the Builders, and then I didn’t like that Divergence revealed too much too quickly, but later books damped those oscillations retroactively.

I like the creative variety in alien forms and civilizations presented here; they seem to fit well. I also like the quietly implied moral present in the reason for the Builders leaving their artifacts lying around: Cooperation is better than conquest.

One thing I didn’t like was the complete silence about the fate of the Zardalu in the latter part of the series. Here’s this ruthless, menacing race whose subjects hated them so much they attempted genocide against them, and everyone has been happy thinking the Zardalu have been dead for thousands of years. Now they’re making a comeback but were discovered while in a position of weakness, and… nothing. Some time was bought by convincing the Zardalu that they’re in danger of being stepped on by other races grown more powerful in the interim, but they have to eventually figure out that’s not the case. No governments have taken any initiative to contain, protect or negotiate with the Zardalu, and their ambassador became little more than a thug and plot device to help the plot in the fifth book. This better be addressed in future books.

The setting of this series is one of the most MOO-like I’ve encountered. It could also potentially make for several good movies or a TV series.

The Complete Fiction of H.P. Lovecraft

As mentioned in previous posts I’ve been on a quest to read all of Lovecraft’s stories. One story I was having a hard time finding was The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, which based on the implications of other stories sounded like it might be one of the most epic. It was, but it was also disappointing in a few ways – the silliness with the cats being first and foremost. It was a good story, but I enjoyed At the Mountains of Madness more.

I was delighted to find a handful of other stories in this volume that I had not previously read.

Free Will by Sam Harris

A short, easy read about the experimental evidence that suggests free will is an illusion, and what it implies for our justice system and for our thoughts about choice and self-determination. I found it a fun and easy read and it extended my awareness of the matter a little by exploring some implications I hadn’t thought of.

God Is Not Great by Christopher Hitchens

I’ve been meaning to read this for a while but it became more opportune when I discovered the audiobook version was on YouTube.

This is a book I’ve been thinking for a long time needs to exist, and I’m glad someone else went to the trouble of writing it so I don’t have to. And that he then read it to me in his nice accent. See the wikipedia article at the title link above for detailed information on the content, but suffice to say he enumerates most of the major things about religion that bother me, and adds more I wasn’t aware of.

Can we abolish this supernatural nonsense now, please?

Schild’s Ladder by Greg Egan

A well-written and interesting hard SF story about a galaxy-threatening accident and the scramble to mitigate it. Less tiresome and more engrossing than some of Egan’s more exposition-heavy, visualization-taxing efforts.

I found it odd that the titular construct played only a tiny role in the story.

The best part of this story, in my opinion, was the interesting model of future human sexuality presented. This is a future where humans are heavily bioengineered and have gotten over their gender-induced hangups. Children do not have genitalia nor do lone adults unless they want to for some odd reason. When two or more people start to develop romantic attachments with each other, their hormonal systems negotiate via pheromones and initiate the growth of appropriate combinations of sex organs based on the emotional dynamics of the relationship. Under this system non-consensual sex is very difficult and sex hormones are less likely to poison rationality.

Pushing Ice by Alastair Reynolds

Quite enjoyed this. It’s a story of survival, discovery and human politics over deep time. But more than anything else it ends as a setup for one or possibly two sequels that I hope will prove as engrossing if they’re ever written.

I require a character in the sequel to use the phrase, “Let’s caul ass!”

Hold Still by Sally Mann

A few years ago, on impulse, I started a collection of books by and about controversial photographers with some half-baked idea of making a study of what gets fussbudgets wound up. So far I only have a couple of autobiographies in the collection, and this is the most recently written of them. I decided to read one to see how one of these photographers reacted to the fuss over her work.

If you don’t know, Sally Mann has several series of photographs that have drawn some flak, but the biggest noise came from nude photos of her own children. She was accused of everything from poor taste to abuse of trust to child pornography.

She seems to have been more naive than photographers would be today (partly thanks to her example), and was taken by surprise by the reaction. She even went to the point of taking her kids and all of her photos of them to an interview with an FBI investigator, and was assured that none of her work was illegal but that she should expect some trouble with stalkers. Sadly, that did come to pass but not as badly as you might fear.

But that story was only a tiny part of the content of this book. This is the story of her life, interweaving the distant history of her family back to her great-grandparents, her unbelievably film-like growing up in the Southern USA – as in “Suthan” – the complex racial situation there that she was oblivious to until adulthood and now has complex feelings about, and her relationships with horses, dogs, men, her children, the land, photography and other artists. It’s all a lot more fascinating than you might expect, and for me it was a window into a very alien lifestyle.

ReWork by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson

This is a fast and easy read; it’s a collection of one-page theses that each attempt to justify a one-sentence quip about how to run a workplace. It came up in the book club at work, which is why I read it.

While I actually agree with a lot of what they say, this book irritates me because it’s written in a very cocksure style. Reading between the lines – and sometimes not between them – the authors are saying, “We ignored conventional wisdom in the following ways and created a small business that happened to be famously successful at the time we decided to publish this book, so therefore we are qualified to assert that this is the Right Way To Do Things.” Even if they’re right, nobody likes braggarts. Actually, especially if they’re right.

There are a few items in this book that I strongly disagree with, though sometimes it’s the presentation that I disagree with. As an example, in the section titled “Build a Rockstar Environment / Skip the Rock Stars” they assert that instead of trying to recruit star talent, employers should try to create a work environment that naturally boosts everyone’s productivity. I think these two things are orthogonal and they’re presenting them in a false dichotomy. It is simultaneously true that the work environment affects everyone’s productivity and that some people are inherently more productive than others. You should do both – create a good environment AND try to hire good people.

Linear Timelapse Robot v1

Just in case anyone is following me via RSS, I just posted a new static page about my latest electronics project, a prototype motion control robot for making timelapse movies.

End of the Roll

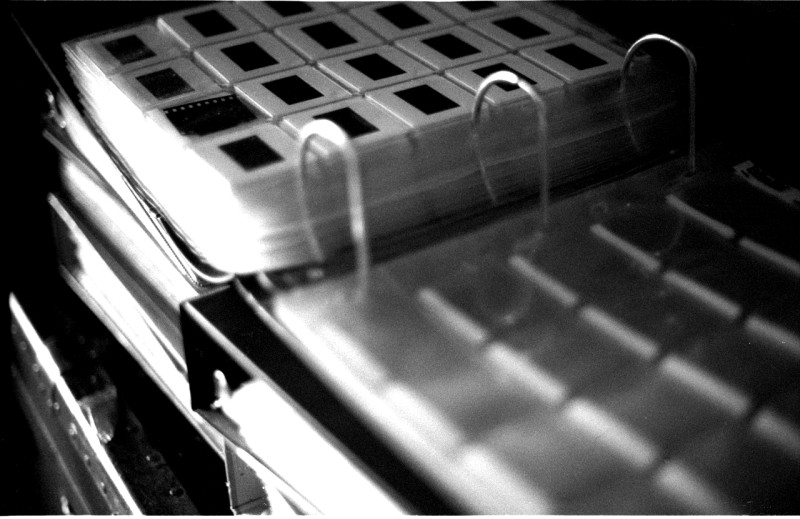

I just finished shooting and scanning my last rolls of photographic film. I’m done shooting film for the foreseeable future, and am going fully digital. Granted those last four rolls have been sitting unused in my fridge for six or seven years already, but their presence bothered me and now that they’re done I have some closure.

With those last rolls out of the way, I also have closure on a project that turned out to be much larger than I expected: Scanning all my film into the computer. In my approximately 32 years of shooting film I amassed 300 rolls, for a total of just over 9,000 images. That may seem tiny compared to what a typical professional film photographer would have, but it takes up to three hours to scan each roll. This scanning job has been done in bits and pieces of my spare time over the last ten years, but if I had been doing it as a full-time job it would have taken me four months!

I bought a dedicated film scanner (Nikon Super CoolScan 5000ED) for this purpose ten years ago, hoping that its batch scanning workflow would help automate the process so I could do other things at the same time. It did, but the scanner software is so flaky that most of the time I got to do other things in parallel just because of the length of time it took to scan each negative; on average I had to scan each film strip image about 1.5 times because of software glitches. Also the batch mode only works for film strips and half my film is mounted slides – but at least scanning individual frames did not expose as many bugs in the software as strips. I considered upgrading to a newer scanner for the latter half of the project, but there were not enough technology improvements to justify the expense.

Anyway, that’s all done now. What’s left is the almost as huge task of cataloging and tagging all my photos. I put a fair bit of effort into researching DAM (Digital Asset Management) software a few years ago and decided on idImager, which appears to have since been rebranded Photo Supreme, as it met more of my requirements for a better price than anything else I looked at. I’ve tried it and quite like it; the tagging and versioning workflow is great, it has some nice bonus features too.

For the record, my 9,000 scanned film photos take up just over 1TB of disk space – I’ve scanned them at 4,800 dpi or higher in 48-bit color, and they don’t compress well because of film grain and sensor noise. A typical image is 120MB big.

I’m really happy to have the scanning project over and done with. That was a lot of work.

This seems like a good time for a retrospective on my personal history with film and film cameras.

When I was a child my mother shot black and white on her Yashica-Mat TLR, and did her own darkroom work. She sometimes let me help with the developing and showed me how to play with the projector to make contact images of household objects and toys – I think that’s where my initial interest came from. It’s magic to shine a light on paper and have a permanent image appear.

—

Keystone 110

The first camera of my own was a generic pocket-sized 110 camera from Consumers Distributing. It had a built-in permanent flash, two focal lengths and a neat in-viewfinder flash ready indicator that I always wondered at the operation of – it was a clever design feature, lighting up despite having no light built in to the indicator. I shot a lot of what I now call tourist/documentary photos on this unit – that is, photos of interesting places and things, but with very little artistic merit to the photos themselves. I was too young to have developed a sense of what makes a photo great, though towards the end of this camera’s long tenure I started experimenting with composition and with panoramas made by taping prints together.

I also used a couple of disposable 110 cameras and one of those ultra-tiny kids’ “spy cameras” from the comic ads, which fits in the gap in the middle of the 110 cartridge.

Examples of pictures I took with the 110:

—

The Polaroid

Later I had a Polaroid instant camera. It was cool to get the photos immediately and the color and clarity were much better than on the 110, but the film was relatively expensive per photo and even as a child I recognized the value of having negatives available for reprints and enlargements. The Polaroid didn’t see frequent use because of its limitations, but it did last a long time.

Examples of pictures I took with the Polaroid:

The Bellows Camera

Also during my tweens I had an old-fashioned bellows camera. I believe it was a Kodak Tourist II given to me by my mother, based on her notes on her own photos. I didn’t use it much and it didn’t make much of an impression on my memory. Eventually the bellows got too many light-permitting punctures for the camera to work well, so I followed nature’s directive and took it apart to see how it was made.

Examples of pictures I took with the bellows camera:

—

The Pink Camera

My first 35mm camera was a cheap fixed-focus tourist model. This was basically the same deal as my 110 but 35mm instead. I no longer remember even what brand it was, but it look vaguely like this only pink. I got quite a bit of use out of it and started to develop a better sense of composition during this time (most of my teens).

Examples of pictures I took with the pink camera:

—

Pentax ESII

For my 20th birthday my parents gave my first “real” (read SLR) camera, a Pentax ESII with a fast 50mm prime lens. This is the film camera I got the most mileage out of, developing my artistic skill and eventually amassing a small collection of used lenses for it. When the electronics eventually failed I bought a second one to replace it, and that’s the camera I just finished shooting some of my last rolls with. I also picked up a Pentax Spotmatic, which uses the same lenses, so I could have two bodies for shoots where I would want to swap lenses a lot. For a while I did my own B&W developing at home too. The Pentax was an excellent, life-altering gift. The vast majority of my film was shot with it and most of my photographic learning was done with it.

Example ESII & Spotmatic photos:

The Crap Pentax

In the early 2000s I picked up a more modern Pentax, used, because I was curious to see what an auto-focus, auto-winding, zoom-lensed camera was like. Unfortunately this model was a bad choice, as it felt cheap and I didn`t like using it. I think I only shot one or two rolls with it, and I no longer remember which ones they were so no examples for this one.

—

The TLR

A few years ago my mother gave me her old Yashica-Mat TLR medium format camera, as she has also gone digital. In the end I only shot a few rolls with it though. It’s a nice camera but I’m put off by the lack of a built-in light meter.

Example TLR photos:

—–

I’m not saying I’ll never shoot film again; it has its applications. But digital is so much cheaper and more convenient and a good digital SLR produces pictures that seem as good, and as enlargeable, as what I shot with my 35mm SLR.

One thing that film does have going for it is its variety of grains and color treatments. Simulating the heavy grain of some B&W films or the weird color cast of cheap 110 film with digital images just doesn’t look the same – at best it evokes nostalgia for those things in those what grew up with them.

I give it twenty years before I develop a weird nostalgia for shooting film and dig out the old cameras.

My Latest Profile Picture: What’s Inside

I’ve recently updated my social media profiles with a new profile picture / avatar, receiving positive response and some curiosity. This is the image, at a high resolution:

This is a picture of me wearing a picture of me. Read on to find out how this was done.

In 2010 the Electronic Arts Capture Lab had an open house, where employees from the rest of the studio could go by for demos of their equipment. See the video in the above link for examples of what we saw.

One thing they demonstrated was the facial capture rig they used to create high-resolution 3D models of actors’ faces. You can see the rig and part of the process between 0:09 and 0:17 in the video at the above link. It’s a rig containing a lot of digital cameras arranged spherically around the subject, and set up to fire in synchrony along with strategically placed flashes. Specialized software then takes all those photographs and correlates the features visible in them to deduce a textured, 3D digital model of the subject. This is one example of the science of photogrammetry. There is a longer discussion of this process in this thread post.

My colleague David Dixon and I had the idea to use these digitized models of our heads to construct actual physical models of our heads, at a larger-than-life scale, and wear them as Halloween costumes.

David, being the 3D editing wizard among the two of us, simplified the models from thousands of polygons down to dozens. Here are before (top) and after (bottom) screenshots of my model showing his work. Note the bottom one uses a corrected version of the skin texture (which I unfortunately lost the high-resolution version of) which explains the differences in skin tone and detail.

You can see the original model had quite a bit of surface noise to be cleaned up, including what looks like fractures in my cheeks but are probably registration errors.

We then imported the simplified model into Tamasoft PepaKura, which segmented it into flattenable pieces and added glue tabs, resulting in many pages of fragments that looked like this:

We had these printed on stiff paper at Staples, then spent hours gluing them together.

Here’s what mine looked like from a few angles the morning I finished it (I worked overnight to finish it in time):

And here are David and I showing them off at the office later that day:

For the profile picture image, I set up a mini studio in my apartment and had my visiting parents help me fit my suit jacket over the shoulders of the model (since I can’t see anything when I’m wearing it) and operate the camera for me. I then digitally emphasized the edges between the polygons and removed the background and replaced it, appropriately, with one of the iconic Max Headroom backgrounds.

So there you have it: A long, technical and involved but creative and fun project that lets me wear an oversized 3D photo of my head over top of my real head.

IR/UV photo experiment

I just picked up an Olympus E-PL1 from a friend, modified for infrared and ultraviolet photography. That basically means the built-in UV/IR filter has been removed, and a filter that blocks most visible light but permits UV and IR light to pass has been placed on the lens.

The weather wasn’t great for experimenting with this today, being overcast and rainy and not many flowers being still in bloom, but the IR results show up pretty well anyway.

Here are some example shots compared with similar shots taken with an unmodified Canon camera. Click to embiggen.

Finally, I tried some quick experiments with compositing the normal and IR shots together. This is a little tricky because I’m combining images from different cameras, different resolutions and different focal lengths, so the registration is poor. Also I haven’t thought of the best way to manipulate the colors yet, but hey, experimentation!